Genre Spotlight: Comic Books/Graphic Novels

BOOM! POW! SLAP! Reading a comic book is like reading a movie. You hear the words and their accompanying sounds, you see the scenes in vivid colors, you (the director) get to point your camera at various angles and shots in ways you can never do simply through prose. Instead of spending paragraphs trying desperately to describe to your readers the visual scene in your head… there it is right in front of us, plain as day. The combination of written and visual arts yields a very unique form of reading and writing. While some (mistakingly) view comics as immature, they’re actually filled with complex themes, gorgeous prose, and incredibly cinematic moments. For those who take issue with the volume of difficulty involved in comic book writing, here are some tips to help:

1) The difference between Comic Book and Graphic Novel

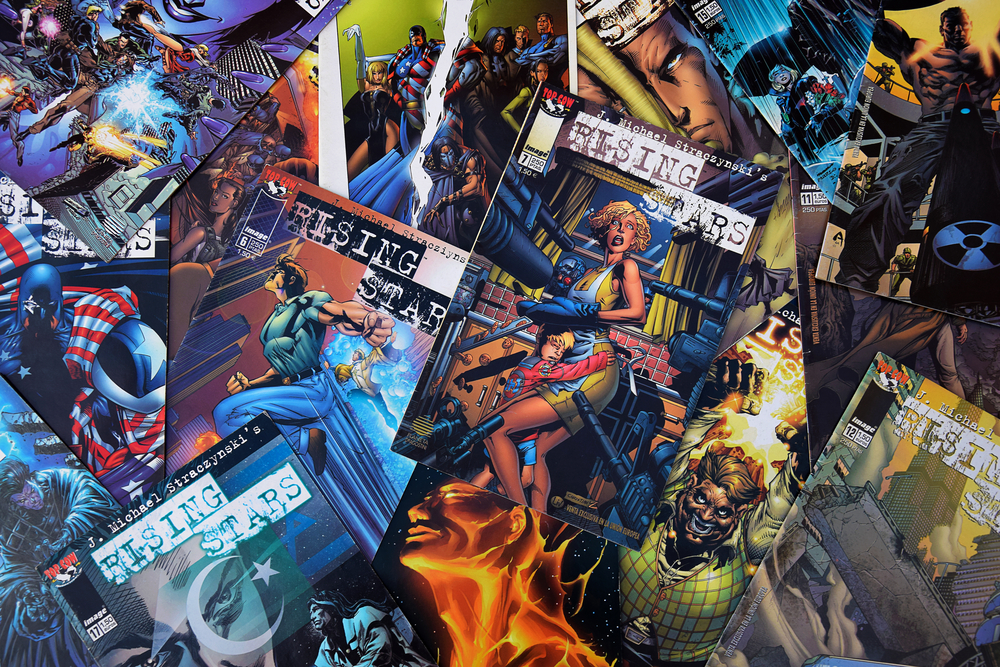

The primary difference between a comic book and a graphic novel is the mode and length of the story-telling. Although superhero comics like Marvel and DC are primarily comic books, the technical definition of the term has little to nothing to do with content. Comic books are serialized stories told over many, very short issues. They typically cover long periods of time in the protagonist’s life rather than one particular event and they span over many issues which correspond with one another.

Graphic novels, on the other hand, are typically individual stories told over one or a few longer issues. These typically detail a particular event, rather than simply spanning over years and various adventures of a protagonist’s life. Because these stories are typically only one or two issues, the plots tend to be much more intricate and complex than that of a comic book because fans aren’t expected to remember details over various issues.

2) Decide which would be best

This is fairly self-explanatory, but (prior to writing) you’ll need to decide which medium would be best for your story. So, for example, let’s say you’re creating your own Batman-like superhero, who will go on various adventures and you’re already overflowing with ideas and origin tales. This will definitely fit better as a comic book than a graphic novel, so you’ll want to keep your issues relatively short. However, let’s say you’re writing a nonfiction story about your specific coming-of-age story. This will be a complete story and, therefore, would work best as a graphic novel. This means you’ll have a lot of writing wiggle room to play around in terms of length and specific scenes you choose to include in the story. If you’re not sure where your story would fit best, do some research to see if you can find a similar book on the market.

3) Find an illustrator

Writing a comic book or graphic novel should be a collaborative process between the writer and the illustrator. All of the greats have done this, including the famed tag team Stan Lee and Kirby. Therefore, it’s best to find your illustrator in the earlier stages of the process. This way you can do a few things. First, you can make sure you’re formatting your script in your chosen illustrator’s preferred way, thus saving you time reformatting later on. Also, your illustrator can serve as someone to bounce ideas off of as far as the visual aspect of the story. A comic book isn’t like any other medium of writing- it is both a visual and a written form of art. It’s only as strong as both of the parts work well together. Seeing the style your story will be in visually may give you ideas on the writing and vice versa. For example, Marvel styled comics like Deadpool are obviously a very different illustration style than The Umbrella Academy series.

The only exception to this rule is if you (like Tillie Walden) will be both the writer and the illustrator, in which case you’ll already have an idea of what your book will look like visually. We’d still encourage you to reach out to other comic book writers to make sure they feel that your illustrations are a good fit with your subject matter. If they don’t fit well, your readers will know (trust us). And (this may go without saying) but write your story before you draw it. Otherwise, it’ll get very messy very quickly.

4) Formatting

Comic books and graphic novels, unlike fiction/nonfiction writing, don’t have an iron-clad standard format across the board. There isn’t a font type, size, formatting design that you see in every comic book writer’s script. If you do some research you’ll see that different people have different styles and preferences on what they prefer in their script. There are, however, a few technical aspects that you’ll see in most comic book or graphic novel scripts.

A header is created for each new page of the graphic novel/comic book. So, your graphic novel page will likely not correspond with the page on Microsoft word. Below the page number, you also create headers for each Panel that will be on the page (Panel One, Panel Two, etc.). The amount that you have per page is entirely up to you and your illustrator (who may have a better idea of how everything will fit together).

Below the Panel label, a comic book writer will typically write a basic description of what the reader is visually seeing in the panel. The length and detail of the description varies greatly between writers, some prefer immense detail to get as close to the picture in their head as possible while others write a brief synopsis and give their illustrator artistic license to play around a bit. Again, this is something that will be decided between you and your artist.

After that, you’ll write below any captions or piece of dialogue that will be included in the panel. It varies how people prefer to have these piece of text written, but we recommend writing them in the order that the viewer is meant to read them. Here are a few suggestions on how to label these pieces of text: Caption 1: [INSERT TEXT], Character 1: [INSERT TEXT] OR 1) Caption:[INSERT TEXT], 2) Character name: [INSERT TEXT].

5) Strong Storytelling

Even though comic books/graphic novels are a shorter medium to tell a story, it’s important that all of the normal facets of a strong story are still present. One mistake that writers often make is focusing too heavily on plot and severely neglecting character development/arc in the story. Make sure, when you’re introducing your protagonist in the story, that you’re immediately giving your reader some character-defining traits. Even if you’re writing a comic and you open on a really dramatic fight scene, have your character go home, take off their costume, sit on their couch in their middle-class house and read The Rime of the Ancient Mariner aloud to their cat. That way you’re still giving us character insight even if you have your heart set on opening with an action scene.

Remember, and this is true of any form of writing: we have to care about your protagonist to care about the events of the story. We know that, with such a short window to write, it can be tempting to submerge the reader in action. But character is still the most important part of the story so make sure you take breaks from the action to let us learn more about your protagonist or even just to give us a funny exchange between them and a friend. Anything that informs us about our protagonist will only serve to strengthen your story and the stakes involved.